Discover the Benefits of Woodlock Oil: A Natural Remedy for Aches and Pains

In today’s fast-paced world, finding effective and natural remedies for muscle aches and pains is crucial for maintaining a healthy lifestyle. One such solution is Wong To Yick Woodlock Oil, a traditional Chinese medicine with a rich history of providing relief from various physical discomforts. In this blog, we will explore the benefits of Woodlock Oil, its ingredients, how to use it effectively, and why it should be a staple in your wellness routine.

What is Wong To Yick Woodlock Oil?

Wong To Yick Woodlock Oil is a medicated oil renowned for its ability to provide soothing relief for muscle aches, joint pains, and other discomforts. Formulated with a blend of natural ingredients, this oil has been used for decades in Chinese medicine to alleviate various physical ailments. It is known for its quick absorption and effectiveness in targeting problem areas.

Key Ingredients and Their Benefits

Woodlock Oil’s unique formulation combines several active ingredients known for their therapeutic properties:

- Methyl Salicylate (50%): Known for its anti-inflammatory properties, methyl salicylate helps reduce swelling and relieve pain in muscles and joints. It works by penetrating deep into the tissues and soothing sore areas.

- Menthol (16%): Menthol provides a cooling sensation that temporarily relieves minor aches and pains. It also helps improve blood circulation in the affected area, promoting faster recovery.

- Camphor (10%): Camphor acts as a counterirritant, stimulating nerve endings to relieve pain and itching. It helps improve blood flow and provides a warming sensation that alleviates discomfort.

How to Use Woodlock Oil

Using Woodlock Oil is simple and convenient. Here’s a step-by-step guide to ensure you get the most out of this powerful remedy:

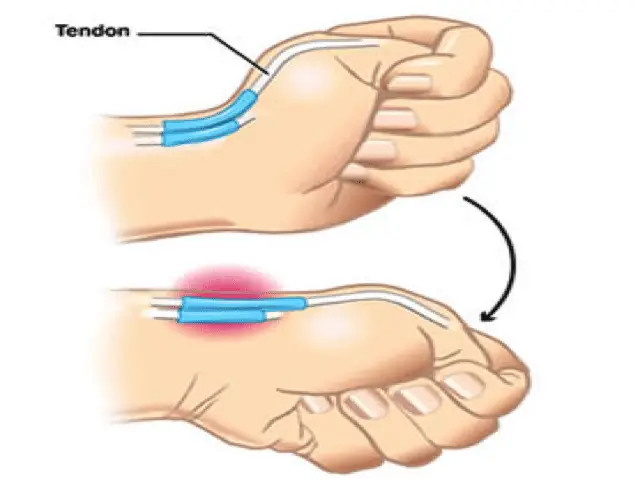

- Identify the Affected Area: Determine the muscle or joint area where you are experiencing discomfort.

- Apply a Small Amount: Pour a few drops of Woodlock Oil onto your palm and gently rub your hands together to warm the oil.

- Massage Gently: Massage the oil onto the affected area using circular motions. Allow the oil to absorb fully into the skin.

- Repeat as Needed: For optimal results, apply the oil up to three or four times daily. Avoid applying to broken skin or sensitive areas.

Benefits of Using Woodlock Oil

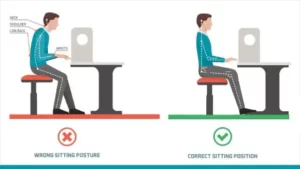

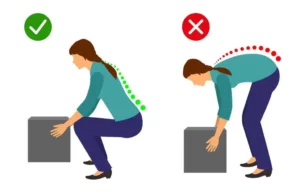

- Fast-Acting Relief: Woodlock Oil’s quick absorption provides fast relief for muscle aches and joint pains, making it a go-to remedy for athletes and active individuals.

- Natural Ingredients: The oil’s natural formulation ensures it is gentle on the skin while delivering powerful therapeutic effects.

- Versatile Use: Whether you’re dealing with sprains, strains, or general muscle soreness, Woodlock Oil is versatile enough to address various physical discomforts.

- Enhances Blood Circulation: The combination of menthol and camphor helps improve circulation, which can speed up the recovery process.

- Trusted Traditional Remedy: With a long history in traditional Chinese medicine, Woodlock Oil is a trusted choice for those seeking natural alternatives to synthetic pain relief products.

Why Choose Woodlock Oil from PhysioFusion?

At PhysioFusion, we are committed to providing high-quality health and wellness products that meet your needs. Our Wong To Yick Woodlock Oil is sourced from reputable manufacturers, ensuring you receive a genuine and effective product. By choosing our Woodlock Oil, you’re opting for a natural remedy backed by decades of tradition and use.

Conclusion

Wong To Yick Woodlock Oil is a versatile and effective solution for managing muscle and joint discomfort. Its natural ingredients and long-standing reputation make it a must-have in your wellness toolkit. Whether you’re an athlete looking for a recovery aid or someone seeking relief from everyday aches, Woodlock Oil offers a powerful solution.

Explore the benefits of Woodlock Oil today and experience the relief you’ve been searching for. Visit our product page to learn more and make your purchase.