THROWING YOUR SHOULDER PAIN AWAY

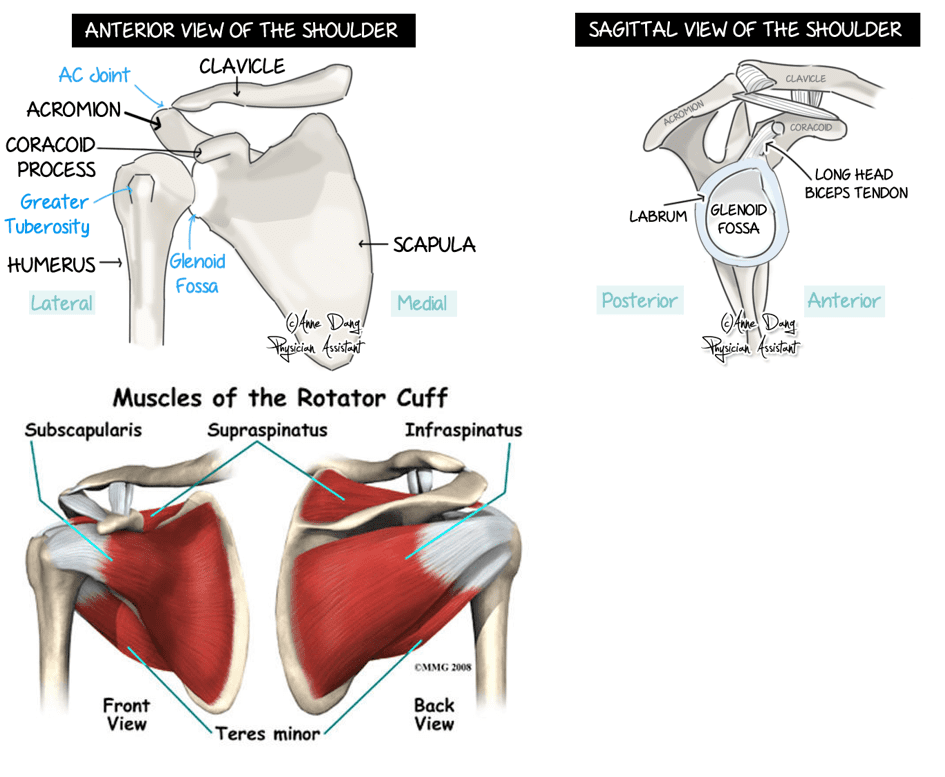

What does the shoulder look like inside?

The shoulder is made up of two joints. These are the acromioclavicular joint (collar bone meets shoulder blade) and the glenohumeral joint (upper arm meets shoulder blade). The shoulder is protected by ligaments (joining bone to bone) and muscles known as the rotator cuff. These muscles form tendons (joining muscle to bone) and play a major role is stabilising the shoulder. Under some of these muscles and tendons, there are small fluid filled sacs ((known as bursae) to allow easy gliding of muscles over bone. The upper arm also joins the shoulder blade with the help of the Labrum (soft tissue around the glenoid cavity). Finally, this is all surrounded by a fluid filled sac which lubricates the shoulder joint for better movement known as the shoulder capsule.

History taking and assessment

You can expect questions regarding the history of your shoulder injury from your physiotherapist such as:

- How the injury happened

- Where the pain is in your shoulder

- Whether you have a ‘dead arm’ feeling

- If you feel a different sensation from the other side or some weakness

- Aggravating and easing activities

- Past history and family history of shoulder injuries or pain

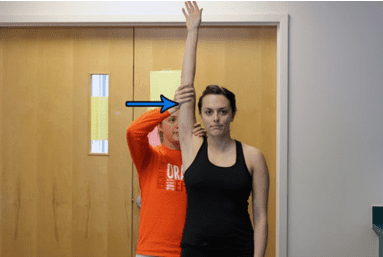

Once these questions have been asked and answered, your physiotherapist will proceed to perform an assessment of you and your shoulder. This can range from:

- Posture assessment

- Strength and sensation testing

- Testing of ROM (movement of the shoulder)

- Special testing to check joint stability, muscle integrity and possible signs of shoulder damage

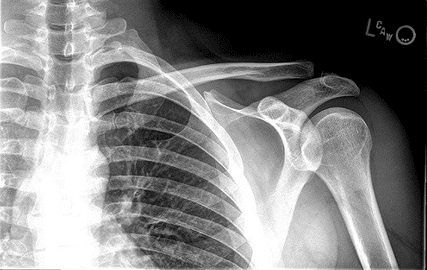

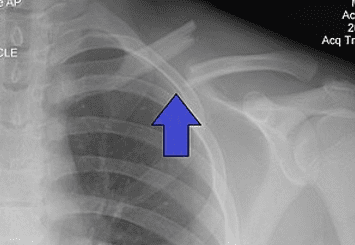

Investigations

Based on your history and examination findings, your clinician will suggest the best possible investigation for you.

In most cases, initial X – rays are done to rule out broken bones.

Ultrasounds can be used to diagnose some ligament and tendon damage such as rotator cuff tears.

MRI is the best form of imaging but this does come at a higher cost and higher exposure to radiation. The MRI scan can identify bone, ligament and tendon injuries in the shoulder.

A CT scan is not usually performed in cases of the shoulder.

Possible injuries to the shoulder

Instability:

If you have dislocated your shoulder in the past or continue to experience shoulder dislocations, you may have some instability of the shoulder. Normally you may develop a “dead arm”. You may also feel a sense of heaviness, numbness or an inability to move the arm which persists for a few minutes. If you are experiencing these episodes more frequently with less force, it is advised that you see your healthcare professional.

Treatment:

Non-surgical management involves a period of rest with a parallel shoulder strengthening program for stability. This is done when the injury is acute and non-recurrent.

Surgical management is opted for when there has been damage to the ligament and Labrum as well as ongoing recurrence of shoulder dislocation. Surgery is associated with a reduced rate of recurrence.

Rotator cuff:

The four muscles that make up the rotator cuff are Supraspinatus, Infraspinatus, Teres Minor and Subscapularis. Rotator cuff injuries are one of the most common disorders of the shoulder. It is believed that most of these injuries are caused by overuse of the shoulder. Often heavy lifting, sports involving the shoulder and repetitive shoulder movements are associated with rotator cuff pathology. These injuries cause pain and stiffness with overhead activity (eg: throwing a ball or putting a shirt on) and pain is worse at night. You may also feel some weakness in your injured arm because of pain.

Treatment:

A partial thickness tear in the rotator cuff can heal with non-surgical management. These are managed with physiotherapy exercises, corticosteroid (cortisone) injections and most importantly, time. It is important to know that the pain will improve over time.

A Full thickness tear in the rotator cuff will normally be managed with surgery. This is followed by immobilisation of the arm for up to 6 weeks in a sling. After these 6 weeks, you should begin a physiotherapy program in order to aid your recovery.

Acromioclavicular joint (ACJ):

This is a fairly common injury and normally occurs in athletes involved in contact sport or when falling directly onto the point of the shoulder. You may experience some pain and swelling in the upper shoulder. This pain can sometimes occur with no reason at all and it is important to voice this to your clinician.

Treatment:

You will be treated surgically or non-surgically according to the severity of your injury.

Non-surgical management includes a brief spell of rest and sling use for protection and healing. This is followed by early mobilisation of the shoulder and a subsequent strengthening program. Your physiotherapist can also assist you with taping in order to return to activity.

Surgical management is followed by a physiotherapy program as outlined by the shoulder surgeon. This is normally done for a quicker return to play in contact sports or when pain is severe and a trial non-surgical management has not worked.

Fractures:

These normally occur as a result of direct trauma to the arm such as a fall. They can be very painful and are usually associated with a lot of swelling around the area.

Treatment:

Depending on where and how severe the injury is, the doctor may opt for surgical or non-surgical management.

In either of these cases, you will undergo a period (6 weeks maximum) of immobilisation of the upper limb to allow for healing. At the end of this period, it is important to see your physiotherapist to begin rehabilitation of your arm.

What to expect

Acute phase:

Immediately following an injury, you should be offered adequate pain relief. A sling can be very effective and can be combined with simple analgesia, anti-inflammatory medications and ice therapy.

Passive range-of-motion (ROM) exercises, including pendulum and active-assisted exercises, should be considered. You will be encouraged to maintain fitness (if comfortable) using a stationary bike or general walking.

Early Rehabilitation phase:

When your pain has settled and your ROM has improved to 60-70% of the unaffected side, you can progress with rehabilitation.

Exercises that might be useful in this phase include:

- Stretch of the shoulder

- Progressive ROM exercises with the goal of achieving full ROM

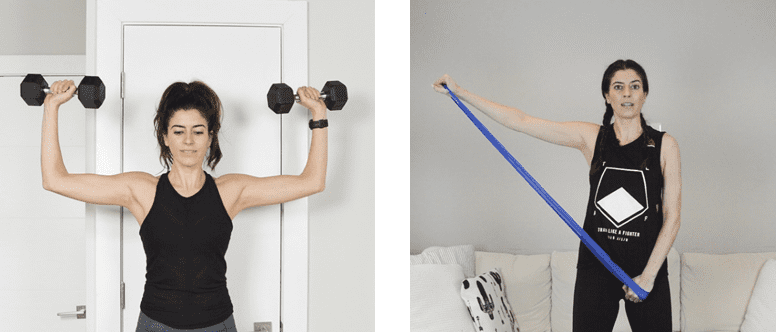

- Strengthening of the rotator cuff and scapular stabilisers

Late Rehabilitation phase:

You will progress to this phase when you have a normal (full and painless) ROM and 75% strength of the unaffected side.

The types of exercises that might be useful in this phase include:

- Progressive multi-planar exercises

- The addition of further resistance exercises, including weights and the use of medicine balls and more functional activity

- Plyometric exercises

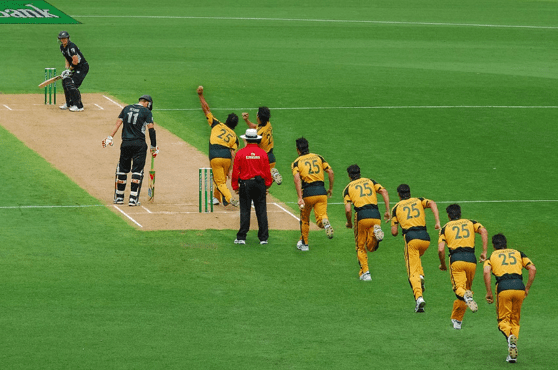

Return to sport:

When you have a normal range of motion and more than 90% strength of the uninjured side, you can progress to return to sport. This should be done in a gradual manner.

A return-to-sport programme may involve:

- Initial unopposed training

- Opposed training in a controlled setting

- Match practice

- Return to sport when this full progression has occurred

In conclusion:

Your shoulder injury will be treated and tailored to you. With most shoulder injuries, physiotherapy can be helpful in operative and non-operative management.

Early management or rehabilitation of your injury could go a long way in speeding up your recovery process and avoiding re-injury in the future.